It is difficult to name a court decision that has had a greater negative impact on recorded music than Bridgeport Music, Inc. v. Dimension Film. The de minimis doctrine, with respect to digital sampling of sound recordings, effectively disappeared after the court’s decision, summarized as: “Get a license or do not sample. We do not see this as stifling creativity in any significant way.” From the perspective of culture theory, the court could not have made a more erroneous statement.

At the time, there was abundant social and political energy associated with hip hop, a genre based on sampling. Hip hop was and still remains an important social and political institution. The appropriation of mainstream culture by the “underground” through digital sampling was a direct, progressive response to disempowerment among the hip hop community. Bridgeport crushed this culture overnight. Samples became the province of the minority of rights holders who owned songs of licensable value, and the minority of musicians and labels who could afford their licensing fees.

Arguments in support of Bridgeport primarily appeal to labor/desert and personhood theories of copyright. Mandating all samples be licensed decimated their widespread use and was a failure from the perspective of cultural theory. But under theories of fairness and personhood, it’s a small price to pay to ensure the original author is compensated, remaining in control of granting or denying permission to sample.

Samples chosen purely for their aesthetic quality are the easiest samples to recreate in a studio, at far less cost than licensing. This is often invoked to defend Bridgeport, but it misses a critical cultural point. Popular songs carry the greatest political and social meaning. Generally speaking, the more popular the song sampled, the larger the audience with whom the meaning will resonate.

In practice, many musicians have transferred their rights to a record label by the time they achieve popularity that warrants being sampled. Particularly with less established artists, a label will avoid the risk of investing in a sampling license when a musician’s sales potential is unproven. Most unsigned musicians can’t afford to license samples at all. This is a chilling of creativity for dubious rewards.

We are compensating yesterday’s musician by erecting a prohibitively expensive barrier of creative entry for today’s musicians. It seems rather contradictory to appeal to the labor/desert theory by raising the cost and bureaucracy of entering the market.

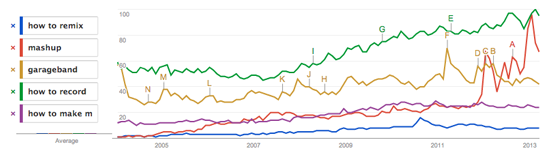

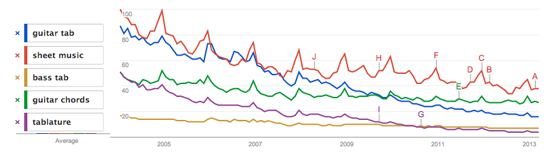

Hip hop adapted and continues to evolve as a central part of our musical culture, but its development as an art form was unquestionably arrested. The near-disappearance of unauthorized digital sampling between 2005 and 2010 has been interrupted by an explosion of creativity. In much the same way hip hop did 30 years ago, mashups and remixes rapidly emerged over the last few years, challenging the sound recording status quo and facing an arrested development of their own.

Today’s sampling musicians lack the history of commercial success hip hop enjoyed. In a way, they don’t know what they’re missing. They feel more entitled to appropriating sound recordings, and less entitled to compensation. They’re participating in what Lawrence Lessig calls a “read-write” culture, similar to the culture of amateur performance that existed prior to the invention of the phonograph and the industrial commodification of music. They’re involved not just in a semiotic democracy, but a new culture of creative consumption that’s productive, not passive. This has numerous implications, not the least of which is that less labor/desert incentives and personhood assurances are needed to stimulate creativity — it now happens as a corollary of consumption.

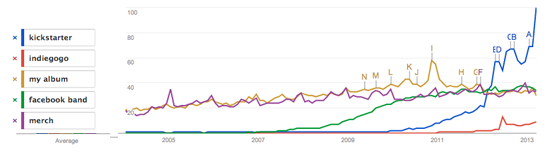

Nothing changed in the law to enable this trend, it’s simply another case of technology racing forward. Songs can now be produced from samples on a tablet in under an hour. Music tastes and popular songs change in weeks, not years. Culture moves at speeds that copyright law can’t keep up with anymore. This creates large financial challenges for “professional” musicians, who are rapidly being offset by an exponentially larger pool of amateur and “semi-pro” musicians.

We must also acknowledge that sound recordings are themselves a platform for music discovery. Sampling can be a way for fans to discover new artists. Having one’s sample appear in the remix of a famous mashup artist can generate huge exposure for an emerging artist. Licensing chills this kind of spontaneous creative reuse, and if one demanded compensation, one may not be sampled. Well-established musicians whose music has demonstrated value do not share the same view, but from a welfare and culture perspective, the greater good is best served by free appropriation.

This is a messy situation, and reform to copyright is needed. A compulsory license for the sampling of sound recordings seems an appropriate solution. The specific mechanisms by which such a license would function are surely more complicated and contentious than, for example, compulsory performance licenses. However, they would be based on well-established legal precedents.

The deadweight loss experienced by our culture when the cost of licensing samples skyrocketed from zero to thousands of dollars was staggering. Cultural theory guides us toward compulsory licensing as a way to foster a more diverse, democratic and equal creative landscape. It encourages us to make works more freely available for creative reuse so that the next generation of musicians can make the next generation of music, while sustaining their livelihoods long enough to pass on their musical traditions.

Creative Commons offers a fine stopgap solution, allowing artists to license music such that it can be freely shared and remixed, yet protected against unauthorized commercial use. As access to music becomes free or nearly free, musicians will need to rely on revenue streams and methods of discovery outside of traditional music retail settings. Today it is more important to live the creative life than achieve the American dream with all the labor/desert it entails. I think that represents the triumph of culture and cultural theory over the increasingly anachronistic theories of copyright which address pre-Digital Age creativity.

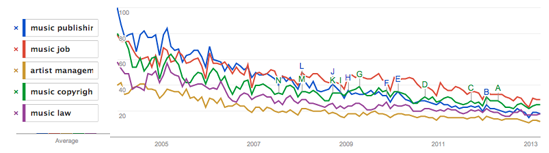

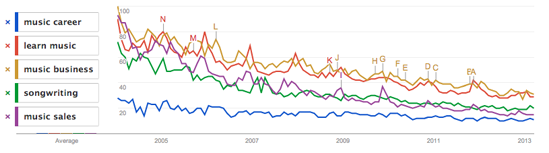

Since Napster was sued out of existence in 2001, the record industry has ruined digital music time and time again. The result has been to stifle innovation and creativity as the industry dug its own grave with respect to consumer support. We will never really know just how much music and culture suffered from their corruption, ineptitude and negligence. But now we can get a rough idea.

Since Napster was sued out of existence in 2001, the record industry has ruined digital music time and time again. The result has been to stifle innovation and creativity as the industry dug its own grave with respect to consumer support. We will never really know just how much music and culture suffered from their corruption, ineptitude and negligence. But now we can get a rough idea.