Hang out for a few minutes and I’ll tell you why Grooveshark may be more ethical than Spotify.

Brief History Lesson

By suing Napster and its kin out of existence, the music industry elite created a “soft landing” for its multi-billion dollar business of selling access to recorded music. They couldn’t kill so-called music “piracy” (also known as song sharing), so they killed the nascent technology companies that tried to build a business around it.

To what extent have musicians benefitted from this business model? Until access to music became free, it was our primary revenue stream. But too often we got such a small piece of the overall pie. The record business was never particularly ethical, with its exploitative contracts, shady accounting and history of corruption.

Free access to music wiped these ethical dilemmas off the table with one click of a mouse, giving us a new debate over the question of whether music should be free to access and share.

Notice I didn’t say “free music”. Music isn’t free to produce or market, though costs have dropped considerably any way you spin it.

At the time of Napster, music suddenly was free to access with an Internet plan and a computer. It took the industry hundreds of millions of legal and lobbying dollars to finally stop the bleeding. In 2013, the slow death of physical media has been largely offset by the rapid growth of digital after a precipitous $3B drop.

The corporate music industry would be quick to tell you that suing innovative digital music companies and individual file sharers was all about protecting musicians’ revenue, that they saved our bottom lines. This is the same industry that coerced us to sign exploitative contracts, that price gouged and price fixed consumers, that bought off radio to play the same songs on repeat.

Nobody’s perfect.

But musicians are starting to wise up as they see the bottom line on their streaming revenue reports. To be fair, Spotify (and iTunes) pay roughly 70% of its revenue to artists (more accurately, “rights holders”, which are primarily the labels who exploit the artists’ copyrights). A lot of the negative reaction can be chalked up to failures in long-term vision — as the decibel point moves right in our royalties, the multiplier grows exponentially. But the current streaming royalty system clearly favors the big four major labels over the short and long term, because it is harder for independent, unsigned and emerging musicians to compete with their massive back catalog of perennially popular music and marketing budget to match.

Some musicians are coming around to bridging the art/business divide and becoming entrepreneurs themselves. They’re sick of having to rely on someone else exploiting their rights for increasingly less money. The Internet allows direct fan patronage in the form of crowdfunding, tipping, or selling both virtual and physical products from one’s own website. Home studio production is getting cheaper and better. Licensees are hungrier than ever for the latest music. Marketing is as easy as creativity > strategy > click. These aren’t empty catch phrases like “downloading music for free is stealing” and “piracy is bad”, these are realities clear to any musician working in the field today.

Yes, there will always be artists who dare not sully their art with business concerns, but they are an increasingly lonely breed. The new musician adapts to the meager streaming royalty stream not by petitioning for higher royalty rates from Pandora, but by embracing business models with far more promise than selling access to recorded music. If only the record business elite would step off. But there’s billions at stake and they like their yachts. Who can blame them? They’re the last generation of the American Dream and they don’t want to wake up.

Occupy the Music Industry

Revolution is blowing in the wind among musician culture, and the industry elite can smell it. The chairman of the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry is acclaimed opera singer Placido Domingo. In the IFPI’s 2012 annual report, Domingo titled his introduction, “A digital world that rewards artists and creators”.

Really? What about “a digital world that rewards the gatekeepers between artists and creators”. That’s really what the IFPI is concerned about. It doesn’t represent the interests of musicians, it safeguards the commercial exploiters of musicians’ recorded music copyrights. Let’s tell it like it is — the money trickles down through the cracks in their multi-billion dollar pavement. The markup on music remains artificially high to justify the expense of major label production and marketing. They also need to even out the variance from gambling on bands like derivatives traders.

What’s concerning is to see musicians jumping on the IFPI’s bandwagon, supporting the suing of technology companies, demonizing their own fans for sharing music. I mean, what do these musicians think is going happen? Are we going to all of the sudden roll the music industry back to 1996 when a CD cost $14.95 and you were forced to buy 9 crappy songs for every hit single?

“Of course not,” these skeptics will tell you. They love new technology, it just has to be applied fairly to musicians. Technology companies, they say, are even worse than the exploitative record labels, because they want to use your music for their own gain and pay you nothing!

It’s not even remotely that simple. Of course, there are plenty of digital music companies exploiting musicians’ copyrights. But it’s precisely because we’re still working within the model of copyright exploitation established by the labels.

Grooveshark is an exploiter. Spotify is an exploiter. And on the face of it, Grooveshark would appear to be screwing artists far worse than Spotify. Google has decided to blacklist them from certain search functions under pressure from the IFPI and its minions to fight so-called “piracy”. But Grooveshark has only been convicted in the industry, not in the court. They’ve literally been blacklisted from the industry for daring to question the status quo of corporate-hijacked music law and technology.

Corporate Hijacking of Music Law and Technology

The majors and some indies have refused to license their music to Grooveshark. As a result, the majors are trying to sue Grooveshark to death just like Napster or all of the other -ster’s they shut down with copyright infringement lawsuits. We know how well that worked — unauthorized song sharing only grew more popular. The industry’s well-documented and cyclical fight on piracy is the same kind of endless war the US is engaged in overseas. The industry has been fighting it for 100+ years and the only true goal has been to co-opt the developments of independent innovators rather than truly eliminate piracy, which is quixotic. (See the book Pop Song Piracy.)

Spotify and its ilk only use officially licensed music. But what happens when the legal system is broken? Copyright is supposed to protect our right to profit from our labor and to express one’s personhood. It’s also supposed to promote social and cultural welfare, and benefit the greater good by making creative works accessible to the widest possible audience. The cost for access is supposed to be high enough to incentivize creators to keep creating, while low enough to prevent a large deadweight loss, depriving the least amount of citizens from access to the work. These are the moral and economic foundations of copyright, and they’ve been hijacked — just like the political process, the food supply and our media — by large corporations.

In 2011, the four major labels controlled 88% of the market share for recorded music. That’s enough to make the Monopoly Man jealous. These labels own the rights to the vast majority of the music we listen to, and use their enormous legal and lobbying resources to keep it that way. It’s not some sort of conspiracy, it’s standard American capitalism, and the American way of music business is increasingly the way of the world.

Don’t Bring Back the $14.95 CD, Bring Back Napster

People rallied around Napster for two reasons. One was that it made it possible to access all of society’s recorded music for free. The second was that many music consumers knew they themselves were being exploited by major labels almost as much as musicians were. They witnessed a history of major music industry settlements for price fixing, price gouging and payola. They heard the stories of great musicians suffering because a label coerced them into an onerous contract. They paid $14.95 for one good song.

The music industry was incapable of embracing a world where all of society’s recorded music was available for free, even if that’s clearly what consumers wanted. (Most people at this point will say, “of course that’s what people wanted, people want everything to be free” to which I reply, “Yes they do.”)

As a quick aside, I believe music is closer to a necessity than a want — closer to food, affection, sex, shelter, etc. than a new TV or a Snickers bar. As a society we should endeavor to provide free and fair access to music — a Right to Music — on a humanitarian level. (Follow the link for more.)

Free access to music is good for musicians for one simple reason: An opportunity to be heard is an opportunity to be paid. Anyway, the best musicians make music in order to be heard first, paid second. The motivating factor of copyright and the potential of being the 1 in 10,000 musicians that become a rock star have been greatly exaggerated. If copyright law evaporated tomorrow we’d still be making music. That the music industry lost half its value and we have more artists creating more music than ever before is testament to this fact.

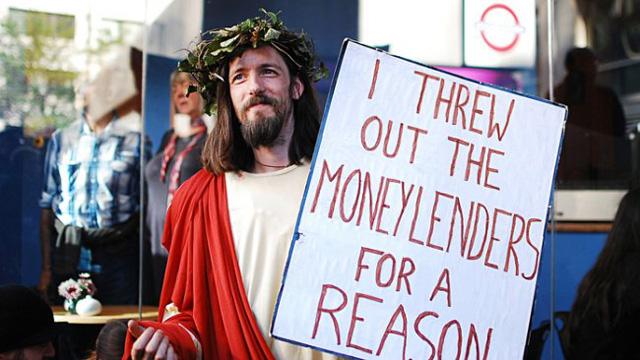

Grooveshark vs. Spotify

This all relates to the Grooveshark vs. Spotify ethics question, because Grooveshark is pretty much the only company of its size that believes access to music should be free (or nearly so.)

Spotify, and the dozens of other streaming services (many of them restricted to certain geographical regions because of licensing rights restrictions) believe that the way to save musicians is to increase payments to the labels that exploit them.

Sound familiar?

Let’s contrast two opinions, the first from IFPI chairman Domingo:

“…policymakers better understand that the internet does not make music “free”.”

Here we have a straight-up threat by the IFPI to stop funding politicians’ re-election campaigns if they don’t pass legislation protecting major labels’ ability to exploit musicians’ rights for maximum profitability. Spotify et. al. would agree with this statement. As we’ve observed, just because the Internet provides free or near-free access to music, that doesn’t make the production and marketing costs of music zero (though costs have inarguably dropped significantly).

Storm the Gates

It seems we are left with two solutions. The one proposed by the IFPI is to protect the gatekeepers by charging a monthly subscription fee for access to music.

I have no problem with this business model, nor do I think should musicians.

I had no problem with it back in 2000 when Napster brought us the technology and proposed the exact same business model. But too many salaries built from exploiting musicians were on the line, and they were sued out of existence. It wasn’t done for the musicians. It was for the executives, the lawyers, the lobbyists and the other business associates at the multi-billion dollar multi-national corporations. Any musician who thinks these companies have their best interests in mind are deluded. It’s not entirely black and white — I’m sure there are plenty of employees who do good and mean well. But even the legends that deserve our respect, like David Geffen, eventually had their ethics compromised by commercial forces. A cursory glance at music industry history clearly demonstrates why gatekeepers between the artist and fan are a really, really bad idea from an ethics standpoint.

Musicians had no choice but to put up with it to get paid. This is no longer true.

That’s why I like option #2 — free access to and sharing of music. (Free as in freedom not free as in beer.)

Let’s contrast Domingo’s threat with Grooveshark SVP Paul Geller’s vision on where the music industry out to be headed:

“…I think that we have to be creative about how to get more money into this ecosystem, because I don’t think anyone sees those numbers [streaming payments] and is really inspired by them, I think people look at them and say ‘well this is a soft landing for the music industry,’ it’s ‘hopefully we don’t have to lay off too many people.’ And that’s why I think that Grooveshark is out there trying to be creative about how to infuse the industry with more money in ways that I don’t think are commonplace right now.” (from Digital Music News)

Grooveshark’s technology and innovation was neck and neck with all the other streaming music sites a few years ago, prior to having to dedicate an enormous chunk of their time and revenue to fighting legal battles with the majors. They recently rolled out some nice new features to compete with the Spotifies, but it’s clear they are living in a legal and fiscal nightmare. Their CEO Sam Tarantino admitted as much while doing an interview for Grooveshark’s new Broadcast feature. I can only surmise by statements like the one above that the people at Grooveshark truly believe they are fighting the good fight. And why shouldn’t they?

Grooveshark does pay artists, it’s just that they haven’t reached a licensing deal with the majors because as of yet they’re unwilling to bend over far enough. To Grooveshark, the majors are just trying to extort them and screw musicians anyway.

If you’re an independent artist or label, you can register your music with Grooveshark and they will pay you a share of their advertising and subscription revenue. These payments may be even smaller than what Spotify can offer, but Grooveshark is also much smaller, and draining their pockets just fighting to exist. Legally, they are in the right, because the DMCA allows for a safe harbor to exist for copyright-infringing, user-generated content, provided the company removes this content upon request and the platform has other significant uses beyond so-called “piracy” (really just unauthorized sharing of songs… does that sound so bad?)

Nobody knows right now if Grooveshark will give out and sign away their seemingly sinking ship to the majors, or if they’ll keep fighting the good fight until the courts deliver a predictably narrow, safe harbor-eroding decision. Law was never good at keeping pace with technology.

Toward a Two-Way Music Industry

The majors would like to continue collecting 88% of the market share for recorded music (and then pay a fraction of it to musicians because they signed exploitative contracts at low points in their career). How does consolidating wealth in media gatekeepers accomplish the IFPI’s mission of achieving “A digital world that rewards artists and creators”?

Stayin’ Alive

This fits into the larger context of corporations and governments trying to kill Internet freedom. Ask yourself, “Why wasn’t radio two-way? Why couldn’t the listeners also be the broadcasters? What about television?” At a glance this seems to be a technology and cost issue, but it’s not that simple. There are powerful commercial forces that ensure these technologies are developed in a way that maximizes profit for corporations, creators and consumers be damned. That’s why we have a long history of gatekeepers in all creative industries, not just in music.

The Internet changed all that with one simple feature — the consumer is now also the broadcaster. Large corporations have spent the last 15 years trying to litigate and legislate their way back to one-way media. Discouragingly, they continue to make gains every day.

This is why I believe Grooveshark may be the more ethical approach on balance. Spotify may talk a good game on paying artists. They may be expanding the pie we take our little piece of. And we can’t rush to conclusions that just because a single stream payment looks small today doesn’t mean it will add up in the long haul. Ultimately, any discussion of musician’s revenue share is taking place within the context of what their revenue share will be after the technology company takes their 30%, and then the label takes its majority share. Spotify and the IFPI are really only innovators in repressive legal maneuvers and artist exploitation. They’re profiting from a 15-year-old idea Napster first realized.

How can I say Spotify and the IFPI are exploiting artists when they’re trying to collect more money for them? Because it perpetuates the old model of exploitation on new technology. It’s repeating the same cycle of co-option that happened with the phonograph, with radio, with cassettes and with CDs. It’s a smokescreen to prevent you from thinking like an entrepreneur, from adapting to free access to music, from finding new opportunities to profit without the gatekeepers and stealing their market share. They desperately want to continue the same systematic exploitation and price-fixing that the record industry has been guilty of for the last 100+ years.

Grooveshark is more ethical because it rejects this corruption. They aren’t saints. They’re certainly pariahs. They haven’t figured out how to improve upon tiny streaming music payments, but they’re trying so hard they’re sacrificing their personal lives, their livelihoods, their reputations and quite possibly their sanity.

The vast majority of musicians will see no significant increase in revenue until the major labels lose their market monopoly, and their revenue share drops considerably. In this sense, Grooveshark is using loopholes in the DMCA to kick the IFPI in the nuts — pretty much its only defense against the obscene legal might of the industry elite.

As a musician, do you really think the IFPI or Spotify (if they can stay in business) are going to solve your revenue problem? Of course not. They’re looking out for #1: the record industry elite.

The solution for musicians is to start looking out for #1 too. That means building a culture of entrepreneurship. That means direct patronage from fans via crowdfunding and tipping. That means cutting out the gatekeeper and giving fans exclusive access to products that are still scarce. Selling access to music is no longer viable, and only by corrupting copyright do corporations make it so. The ethical foundation of copyright is sound, but it has been corrupted.

The greatest lie told by the IFPI is not that their mission is driven by musicians (they have musicians in mind, maybe, but certainly not a priority). The greatest lie told is that they are somehow going to bring musicians back to a world where they were fairly paid for their labor, where they are free to express their personhood without exploitation, where society can access and share music freely, and where more music of higher quality and greater diversity is listened to with greater frequency.

That world never existed. But it can today, with free access to music as the great equalizer.

The only way to fairly solve the musician revenue problem is for musicians to reject the century-old system of exploitation and fight to keep the Internet free so we can build a new culture and economy of direct fan patronage and musician entrepreneurship.

Until that happens, I’ll be rocking out to Placido Domingo on Grooveshark and waiting for the next Napster.